Marty Robbins In Depth - Part Two

First published in Country Music People, April 1975

This was the beginning of Marty Robbins’ flirtation with rock‘n’roll. At first his rock‘n’roll records like Maybelline, Mean Mama Blues and Pretty Mama kept to a kind of up-tempo country backing. Surprisingly some of these tunes were penned by Robbins, the first indication of the kind of versatility he was to demonstrate throughout his career, a versatility that kept him head and shoulders above so many country artists for the past fifteen years.

Marty’s first big hit didn’t come until 1956 when he released Singing The Blues, a Melvin Endsley song that established Marty in the pop field as well as topping the country charts.

This song is often regarded as pop, probably because of the cover versions by Guy Mitchell and Tommy Steele. Marty handled it with style, adding some rare falsetto notes over the top of a bassy, but countrified backing. At the time of this success Marty recorded a few duets with songwriter Lee Emerson. Lee has worked alongside Robbins for years, providing him with songs and at one time being a regular member of his touring show. The duets usually featured Emerson singing lead with Marty doing a sort of ‘back-up vocal.’

Following the success of Singing The Blues it was decided that it would be a good thing to take Marty to New York, give him a different sound and try to get him across to the new pop audience that was beginning to emerge around the world.

The middle-aged men who ran the record business believed that this new teenage music was a passing fad. They believed within a few short years it would all be forgotten, so they tried to cash in as soon as possible.

While in New York, Marty recorded with two of the older men of the music business, Mitch Miller and Ray Coniff. As well as his own songs like A White Sport Coat (And A Pink Carnation) he also cut Burt Bacharach’s Story Of My Life and the Tepper-Bennett partnership’s Stairway Of Love. Robbins sang well on these teenage pop songs, but they were riddled with bo-poop-a-doop two beat fol-de-rol of a kind that makes strong men wilt. The move to New York served its purpose though. Marty Robbins broke through to mass acceptance as first A White Sport Coat topped the pop charts, then half-a-dozen other simple pop tunes followed. For a brief period Marty Robbins became one of the top pop idols in the States and his name was known from coast to coast. After years of struggling, Marty Robbins had made it to the top, in a way that must have been as a big a surprise to him, as much as it was to his country audience.

With this kind of success came Marty’s first album release, SONG OF ROBBINS. This was an event that must have brought joy to those country fans who thought that Marty had forsaken country music for the headlines and bright lines of New York. With a simple, plaintive country backing of fiddles, piano, steel guitar and light drumming, he sang a selection of sad, country tunes.

Most of these, like Lovesick Blues, Bouquet Of Roses and Have I Told You Lately That I Love You are well known to country fans and Robbins makes every word count. Maybe it’s the way he puts his own special stamp on each song that makes it sound so personal. But you have no doubt when you hear Robbins sing these songs that he means every word he’s singing.

Down through the years songs that tell a story have been the most popular in country music. Whether they be true tales or a figment of the writer’s imagination, as long as they are credible and contain an easily understood philosophy, then they are guaranteed of lasting success.

Marty Robbins has this natural knack for telling a story in song, a talent that first came to light with his famous cowboy ballads of the early 1960s. It was a period in the American music business when unearthing old folk tunes was in vogue. At the tail end of the rock‘n’roll boom of the mid-1950s, songs like Tom Dooley, Battle Of New Orleans and Springtime In Alaska all became big pop hits.

They were termed at the time ‘saga songs.’ They were in fact folk songs, many passed down through the years, others written around events that had taken place, with the writer adding flourishes to the original event to create a wider interest in the song. Because of his background as a rancher, along with his formative years spent in New Mexico and Arizona, Marty Robbins was able to walk into this new fad better equipped than most, with a style all of his very own.

Borrowing heavily from the stylings of The Sons Of Pioneers, but with a natural love of cowboy music and a composing ability second-to-none, he was able to come up with a series of classic cowboy ballads that still sound as fresh and exciting as the first time I heard them fifteen years ago.

The songs were written with a conscious effort to recreate the sound or style of an earlier era. Despite the stylistic excellence, like the puppet figures you see in western movies, these cowboy ballads were never more than an imitation of the real thing. But Robbins knew what he was singing about. This is what made them sound so convincing. The songs had strong imagery, vividness, and sense of realism, or more accurately, naturalism.

The first album of GUNFIGHTER BALLADS, released in 1959, featured two epic Robbins’ compositions El Paso was a long song for a single release, let alone a million-seller. It told in graphic terms the story of a gunfighter and his love for Feleena. The tale unfolds to the strumming of Spanish guitars in the background, Robbins sings in an unhurried way, allowing the song to fall out slowly, making every word count. It is important with a song like this that every twist and turn is fully understood. The harmony and falsetto voices are used to perfection, keeping the listener on the edge of his seat. It’s pure magic the way Robbins can keep you pinned down with a song like this. You dare not move, you may miss an exciting instalment, the atmosphere throughout the song is chilling.

The myth of the gunfighter has fed the cinema screen with many tales, but very rarely does the excitement come alive quite the same in song. Marty Robbins proved with Big Iron that a song about a gunfight could be thrilling, exciting, and more important, commercial. Again the accompaniment is simple, the guitar work helps build the song, but it is really down to the words and Robbins’ wonderfully expressive voice.

Many times Marty Robbins has been accused of glossing over the life of the cowboy; well he may not have the same hard-edged, rough-hewn vocal styling of the cowboy singers of the 1920s and 1930s, but he has, through his smooth cowboy ballads, introduced a lot of people to country music.

Since this initial success with cowboy ballads, Marty Robbins has revisited the scene several times on record, producing four more albums of similar material. MORE GUNFIGHTER BALLADS released in 1960 features San Angelo, almost a sequel to El Paso. Of better quality is Tompall Glaser’s Five Brothers and Joe Babcock’s exciting Prairie Fire. You can almost feel the flames licking at your feet as Robbins and his group with rare dramatic power build this song up to a thrilling climax.

Whenever and wherever he performs Robbins always incorporates his cowboy ballads into his act. Whether it be at Carnegie Hall, a night spot in Las Vegas, or on stage at the Opry, you can be sure this man will never forget his roots. In the mid-1960s he produced and starred in a television series called The Drifter. Some of the songs he sang in this series were included on the album, THE DRIFTER. The production and sound was very much in keeping with his previous albums and once again Marty was able to demonstrate his talent at painting portraits of the West in song.

The standout on this album is his own Mr. Shorty. A tale of a small man put down wherever he goes, but quite able to stand up for himself, Robbins brings a tension to the song and a sardonic humour that makes it one of the finest pieces he has ever written. Another piece of brilliant western writing is Bobby Sykes’ Cottonwood Tree. As the title implies, it is all about hanging and the pathos that is painted in this simple tale brings a lump in my throat each time I hear it.

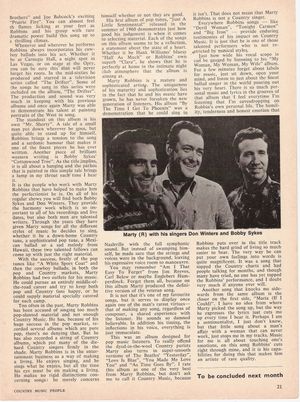

It is the people who work with Marty Robbins that have helped to make him the perfectionist he is. On all of his regular shows you will find both Bobby Sykes and Don Winters. They provide the harmony work which is so important to all of his recordings and live dates, but also both men are talented writers. Through the years they have given Marty songs for all the different styles of music he decides to sing, whether it be a down-home country tune, a sophisticated pop tune, a Mexican ballad or a sad melody from Hawaii, these two talented fellows can come up with just the right material.

With the success, firstly of the pop tunes like A White Sport Coat and then the cowboy ballads, in both the pop and country markets, Marty Robbins had two outlets for his music. He could pursue an entirely middle-of-the-road career and try to keep both pop and country fans happy, or he could supply material specially catered for each camp.

Too often in the past, Marty Robbins has been accused of singing too much pop-slanted material and not enough country music. He has, because of his huge success in the pop market, recorded several albums which are pure pop, there’s no denying that. But he has also recorded a string of country albums, which put many of the die-hard country singers firmly in the shade. Marty Robbins is in the entertainment business as a way of making a living. He enjoys singing, and he sings what he enjoys, but all the time his eye must be on making a living. He makes no rigid distinctions concerning songs: he merely concerns himself whether or not they are good.

His first album of pop tunes JUST A LITTLE SENTIMENTAL released in the summer of 1960 demonstrates just how good his judgement is when it comes to selecting material. Each of the songs on this album seems to be a reflection, a statement about the state of a heart. Whether it be Hank Williams’ bluesy Half As Much or Robbins’ own superb Clara, he shows that he is perfectly at home in the intimate night club atmosphere that the album is aiming at.

Marty Robbins is a mature and sophisticated artist. The uniqueness of his maturity and sophistication lies in the fact that he and his music have grown, he has never forsaken the new generation listeners. His album BY THE TIME I GET TO PHOENIX was a demonstration that he could sing in Nashville with the full symphonic sound. But instead of swamping himself, he made sure that the strings and voices were in the background leaving his expressive voice room to manoeuvre.

You may remember Am I That Easy To Forget from Jim Reeves, Carl Belew or maybe Englebert Humperdinck. Forget them all, because on this album Marty produced the definitive version of the veteran song.

It is not that it’s one of my favourite songs, but it serves to display once again one of the man’s rarest virtues—that of making any song, regardless of composer, a shared experience with the listener. He sounds so damned believable. In addition his timing, the inflections in his voice, everything is just immaculate.

This was an album designed for pop music listeners. To really offend the dyed-in-the-wool country purists Marty also turns in super-smooth versions of The Beatles’ Yesterday and such standards as Love Is Blue, You Made Me Love You and As Time Goes By. I rate this album as one of the very best from Marty Robbins, but don’t ask me to call it country music, because it isn’t. That does not mean that Marty Robbins is not a country singer.

Everything Robbins sings—like Devil Woman, Tonight Carmen and Big Iron—provide enduring testimonies of his impact on country music. It is just that he is one of those talented performers who is not restricted by musical styles.

Just how wide his vocal scope is can be gauged by listening to his MY WOMAN, MY WOMAN, MY WIFE album. For a few minutes forget about labels for music, just sit down, open your mind, and listen to just about the finest ballad singer in the world pouring out his very heart. There is so much personal music and lyrics in the grooves of that album that I feel everytime I’m listening that I’m eavesdropping on Robbins’ own personal life. The humility, tenderness and honest emotion that Robbins puts over in the title track makes the hard grind of living so much easier to bear. The very way he can put your own feelings into words is quite magnificent. It was a song that topped the country charts and had people talking for months, and though many have tried, no one had yet topped the Robbins’ performance and I doubt very much if anyone ever will.

Another song that knocks me sidewards from the same album is the closer on the first side, Maria (If I Could). I have no idea from where Marty picked the song up, but the way he expressed the lyrics just cuts me up every time I hear it. Perhaps I’m a sentimentalist, I just don’t know, but that little song about a man’s affair with a woman that can never work, just stops me in my tracks. Music for me is all about touching one’s emotions, on this song Robbins cuts right through mine, and it is his capabilities for doing this that makes him an artist of rare quality.

Continued in May issue

This was the beginning of Marty Robbins’ flirtation with rock‘n’roll. At first his rock‘n’roll records like Maybelline, Mean Mama Blues and Pretty Mama kept to a kind of up-tempo country backing. Surprisingly some of these tunes were penned by Robbins, the first indication of the kind of versatility he was to demonstrate throughout his career, a versatility that kept him head and shoulders above so many country artists for the past fifteen years.

Marty’s first big hit didn’t come until 1956 when he released Singing The Blues, a Melvin Endsley song that established Marty in the pop field as well as topping the country charts.

This song is often regarded as pop, probably because of the cover versions by Guy Mitchell and Tommy Steele. Marty handled it with style, adding some rare falsetto notes over the top of a bassy, but countrified backing. At the time of this success Marty recorded a few duets with songwriter Lee Emerson. Lee has worked alongside Robbins for years, providing him with songs and at one time being a regular member of his touring show. The duets usually featured Emerson singing lead with Marty doing a sort of ‘back-up vocal.’

Following the success of Singing The Blues it was decided that it would be a good thing to take Marty to New York, give him a different sound and try to get him across to the new pop audience that was beginning to emerge around the world.

The middle-aged men who ran the record business believed that this new teenage music was a passing fad. They believed within a few short years it would all be forgotten, so they tried to cash in as soon as possible.

While in New York, Marty recorded with two of the older men of the music business, Mitch Miller and Ray Coniff. As well as his own songs like A White Sport Coat (And A Pink Carnation) he also cut Burt Bacharach’s Story Of My Life and the Tepper-Bennett partnership’s Stairway Of Love. Robbins sang well on these teenage pop songs, but they were riddled with bo-poop-a-doop two beat fol-de-rol of a kind that makes strong men wilt. The move to New York served its purpose though. Marty Robbins broke through to mass acceptance as first A White Sport Coat topped the pop charts, then half-a-dozen other simple pop tunes followed. For a brief period Marty Robbins became one of the top pop idols in the States and his name was known from coast to coast. After years of struggling, Marty Robbins had made it to the top, in a way that must have been as a big a surprise to him, as much as it was to his country audience.

With this kind of success came Marty’s first album release, SONG OF ROBBINS. This was an event that must have brought joy to those country fans who thought that Marty had forsaken country music for the headlines and bright lines of New York. With a simple, plaintive country backing of fiddles, piano, steel guitar and light drumming, he sang a selection of sad, country tunes.

Most of these, like Lovesick Blues, Bouquet Of Roses and Have I Told You Lately That I Love You are well known to country fans and Robbins makes every word count. Maybe it’s the way he puts his own special stamp on each song that makes it sound so personal. But you have no doubt when you hear Robbins sing these songs that he means every word he’s singing.

Down through the years songs that tell a story have been the most popular in country music. Whether they be true tales or a figment of the writer’s imagination, as long as they are credible and contain an easily understood philosophy, then they are guaranteed of lasting success.

Marty Robbins has this natural knack for telling a story in song, a talent that first came to light with his famous cowboy ballads of the early 1960s. It was a period in the American music business when unearthing old folk tunes was in vogue. At the tail end of the rock‘n’roll boom of the mid-1950s, songs like Tom Dooley, Battle Of New Orleans and Springtime In Alaska all became big pop hits.

They were termed at the time ‘saga songs.’ They were in fact folk songs, many passed down through the years, others written around events that had taken place, with the writer adding flourishes to the original event to create a wider interest in the song. Because of his background as a rancher, along with his formative years spent in New Mexico and Arizona, Marty Robbins was able to walk into this new fad better equipped than most, with a style all of his very own.

Borrowing heavily from the stylings of The Sons Of Pioneers, but with a natural love of cowboy music and a composing ability second-to-none, he was able to come up with a series of classic cowboy ballads that still sound as fresh and exciting as the first time I heard them fifteen years ago.

The songs were written with a conscious effort to recreate the sound or style of an earlier era. Despite the stylistic excellence, like the puppet figures you see in western movies, these cowboy ballads were never more than an imitation of the real thing. But Robbins knew what he was singing about. This is what made them sound so convincing. The songs had strong imagery, vividness, and sense of realism, or more accurately, naturalism.

The first album of GUNFIGHTER BALLADS, released in 1959, featured two epic Robbins’ compositions El Paso was a long song for a single release, let alone a million-seller. It told in graphic terms the story of a gunfighter and his love for Feleena. The tale unfolds to the strumming of Spanish guitars in the background, Robbins sings in an unhurried way, allowing the song to fall out slowly, making every word count. It is important with a song like this that every twist and turn is fully understood. The harmony and falsetto voices are used to perfection, keeping the listener on the edge of his seat. It’s pure magic the way Robbins can keep you pinned down with a song like this. You dare not move, you may miss an exciting instalment, the atmosphere throughout the song is chilling.

The myth of the gunfighter has fed the cinema screen with many tales, but very rarely does the excitement come alive quite the same in song. Marty Robbins proved with Big Iron that a song about a gunfight could be thrilling, exciting, and more important, commercial. Again the accompaniment is simple, the guitar work helps build the song, but it is really down to the words and Robbins’ wonderfully expressive voice.

Many times Marty Robbins has been accused of glossing over the life of the cowboy; well he may not have the same hard-edged, rough-hewn vocal styling of the cowboy singers of the 1920s and 1930s, but he has, through his smooth cowboy ballads, introduced a lot of people to country music.

Since this initial success with cowboy ballads, Marty Robbins has revisited the scene several times on record, producing four more albums of similar material. MORE GUNFIGHTER BALLADS released in 1960 features San Angelo, almost a sequel to El Paso. Of better quality is Tompall Glaser’s Five Brothers and Joe Babcock’s exciting Prairie Fire. You can almost feel the flames licking at your feet as Robbins and his group with rare dramatic power build this song up to a thrilling climax.

Whenever and wherever he performs Robbins always incorporates his cowboy ballads into his act. Whether it be at Carnegie Hall, a night spot in Las Vegas, or on stage at the Opry, you can be sure this man will never forget his roots. In the mid-1960s he produced and starred in a television series called The Drifter. Some of the songs he sang in this series were included on the album, THE DRIFTER. The production and sound was very much in keeping with his previous albums and once again Marty was able to demonstrate his talent at painting portraits of the West in song.

The standout on this album is his own Mr. Shorty. A tale of a small man put down wherever he goes, but quite able to stand up for himself, Robbins brings a tension to the song and a sardonic humour that makes it one of the finest pieces he has ever written. Another piece of brilliant western writing is Bobby Sykes’ Cottonwood Tree. As the title implies, it is all about hanging and the pathos that is painted in this simple tale brings a lump in my throat each time I hear it.

It is the people who work with Marty Robbins that have helped to make him the perfectionist he is. On all of his regular shows you will find both Bobby Sykes and Don Winters. They provide the harmony work which is so important to all of his recordings and live dates, but also both men are talented writers. Through the years they have given Marty songs for all the different styles of music he decides to sing, whether it be a down-home country tune, a sophisticated pop tune, a Mexican ballad or a sad melody from Hawaii, these two talented fellows can come up with just the right material.

With the success, firstly of the pop tunes like A White Sport Coat and then the cowboy ballads, in both the pop and country markets, Marty Robbins had two outlets for his music. He could pursue an entirely middle-of-the-road career and try to keep both pop and country fans happy, or he could supply material specially catered for each camp.

Too often in the past, Marty Robbins has been accused of singing too much pop-slanted material and not enough country music. He has, because of his huge success in the pop market, recorded several albums which are pure pop, there’s no denying that. But he has also recorded a string of country albums, which put many of the die-hard country singers firmly in the shade. Marty Robbins is in the entertainment business as a way of making a living. He enjoys singing, and he sings what he enjoys, but all the time his eye must be on making a living. He makes no rigid distinctions concerning songs: he merely concerns himself whether or not they are good.

His first album of pop tunes JUST A LITTLE SENTIMENTAL released in the summer of 1960 demonstrates just how good his judgement is when it comes to selecting material. Each of the songs on this album seems to be a reflection, a statement about the state of a heart. Whether it be Hank Williams’ bluesy Half As Much or Robbins’ own superb Clara, he shows that he is perfectly at home in the intimate night club atmosphere that the album is aiming at.

Marty Robbins is a mature and sophisticated artist. The uniqueness of his maturity and sophistication lies in the fact that he and his music have grown, he has never forsaken the new generation listeners. His album BY THE TIME I GET TO PHOENIX was a demonstration that he could sing in Nashville with the full symphonic sound. But instead of swamping himself, he made sure that the strings and voices were in the background leaving his expressive voice room to manoeuvre.

You may remember Am I That Easy To Forget from Jim Reeves, Carl Belew or maybe Englebert Humperdinck. Forget them all, because on this album Marty produced the definitive version of the veteran song.

It is not that it’s one of my favourite songs, but it serves to display once again one of the man’s rarest virtues—that of making any song, regardless of composer, a shared experience with the listener. He sounds so damned believable. In addition his timing, the inflections in his voice, everything is just immaculate.

This was an album designed for pop music listeners. To really offend the dyed-in-the-wool country purists Marty also turns in super-smooth versions of The Beatles’ Yesterday and such standards as Love Is Blue, You Made Me Love You and As Time Goes By. I rate this album as one of the very best from Marty Robbins, but don’t ask me to call it country music, because it isn’t. That does not mean that Marty Robbins is not a country singer.

Everything Robbins sings—like Devil Woman, Tonight Carmen and Big Iron—provide enduring testimonies of his impact on country music. It is just that he is one of those talented performers who is not restricted by musical styles.

Just how wide his vocal scope is can be gauged by listening to his MY WOMAN, MY WOMAN, MY WIFE album. For a few minutes forget about labels for music, just sit down, open your mind, and listen to just about the finest ballad singer in the world pouring out his very heart. There is so much personal music and lyrics in the grooves of that album that I feel everytime I’m listening that I’m eavesdropping on Robbins’ own personal life. The humility, tenderness and honest emotion that Robbins puts over in the title track makes the hard grind of living so much easier to bear. The very way he can put your own feelings into words is quite magnificent. It was a song that topped the country charts and had people talking for months, and though many have tried, no one had yet topped the Robbins’ performance and I doubt very much if anyone ever will.

Another song that knocks me sidewards from the same album is the closer on the first side, Maria (If I Could). I have no idea from where Marty picked the song up, but the way he expressed the lyrics just cuts me up every time I hear it. Perhaps I’m a sentimentalist, I just don’t know, but that little song about a man’s affair with a woman that can never work, just stops me in my tracks. Music for me is all about touching one’s emotions, on this song Robbins cuts right through mine, and it is his capabilities for doing this that makes him an artist of rare quality.

Continued in May issue