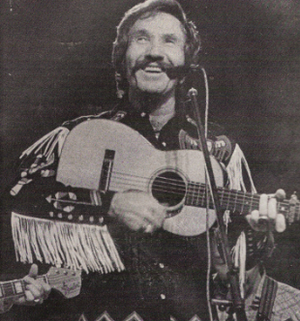

Marty Robbins

First published in Country Music People, April 1978

Marty Robbins! Here is a man who has been a successful country music star for more than twenty-five years. A top class singer, outstanding songwriter and brilliant entertainer whose talent seems to know no boundaries.

Marty Robbins! Here is a man who has been a successful country music star for more than twenty-five years. A top class singer, outstanding songwriter and brilliant entertainer whose talent seems to know no boundaries.

It was Easter 1975 when he made his British debut at Wembley. He had put off coming to Britain on previous occasions because he hadn’t enjoyed any sort of chart success in years. He need never have worried. He does of course have an illustrious background and he went through many of his most famous songs like El Paso, Ribbon Of Darkness, Tonight Carmen and Devil Woman, all sung faultlessly and with a life and originality about his style of delivery that was absent from most of the other performers.

His reputation was greatly enhanced the following year by a return appearance at Wembley and a short concert tour which delighted his fans and introduced him to a lot of people who only vaguely knew of his work and never appreciated his high standard of entertaining.

His charismatic performances were a revelation, his vocal style and degree of control just a magical experience. Yet there has been a lot of criticism of Marty’s record releases of late by people who only wish him well, and could even be counted as ‘fans’—the words ‘similarity’ and even ‘boring’ have begun creeping in.

Robbins’ style is his greatness and obviously this is what he wishes to consolidate. Wisely he doesn’t let himself become burdened down or limited to a specific style. He could, if he so wished, follow so many of the other top country names and pad his albums up with the current hits, but Marty has never been one to follow trends.

Back in 1959 he went against the trend, writing and recording a string of cowboy ballads. In 1962 it was an Hawaiian flavoured song, Devil Woman, that brought him more international success. Three years later he jumped the gun again and was the first country artist to record a Gordon Lightfoot song—Ribbon Of Darkness. It proved to be the beginning of folk-country, a style that launched Waylon Jennings, George Hamilton IV and Bobby Bare high into the country charts.

During Marty’s last British tour in April 1976, he took time out from a busy schedule to speak to me at length about his career, plans for the future and the material that he has recorded down through the years. Like so many recording artists, Marty is inundated with songs from aspiring writers. With more than three hundred of his own songs to his credit, Marty can, naturally, be choosy as to what he records.

“All too often songwriters will send me Marty Robbins’ type songs. I don’t need them, I can write those myself. I’m always on the look out for songs that are different,” Marty explains. “This is how I came to record Singing The Blues. It was submitted by Melvyn Endsley, a very talented writer. At the time I remember him playing all these sad ballads which were in the style I had back in the early fifties, then suddenly there was this song that was completely different. It was Singing The Blues and I was really enthusiastic about it.”

Even today it is amazing the number of people who think that either Singing The Blues, A White Sport Coat or El Paso were Marty’s first recordings. But you must go back a bit further to 1952 for Marty’s initial work. In fact, before Singing The Blues was released in the autumn of 1956, Marty had released twenty-two singles.

They illustrated the ultimate in pure country music. Most of the songs like I’ll Go On Alone, Sing Me Something Sentimental, Love Me Or Leave Me Alone and Pretty Words being written by the singer. There was a central theme in his writing for most of those singles which has since been diffused into a pot-pourri of themes and styles.

One of country music’s most effective writers, Marty not only dwells on the beauties of approval, but also examines the sadness and lack of confidence that results when one experiences rejection. He sings of broken romance as his loved one leaves in Tomorrow You’ll Be Gone, a simple piece of lyrical poetry backed up by beautiful steel guitar that seems to cry with Robbins as he pours his heart out. It was one of the finest debut records of the time.

I asked Marty about these early recordings, which were mainly recorded in Dallas, Texas. How did he feel about their apparent rejection by the country fans at the time.

His reply showed how little we fully understand the American country music scene of the mid-1950s. “Well, to me at the time, I was successful. I was singing and playing my own songs, and though they didn’t exactly top the charts, it certainly didn’t worry me. I was just so happy to be recording and appearing in front of audiences for a living.”

Marty’s talent at the time certainly didn’t go unnoticed. The late Fred Rose flew out to Phoenix to sign him as a writer with Acuff-Rose towards the end of 1951 and this proved to be one of their best investments. “I was really proud to be signed up by Fred Rose. He taught me a lot about the ethics of being a songwriter. In the early days, several of the big stars, you know, I can’t name them, offered to record my songs if I would give them a share of the song. There’s no way I would do that. They were my songs, a part of my life, and I certainly was not prepared to give any of that away.”

But Marty’s songs did get recorded with Webb Price recording I’ll Go On Alone and other stars like Hank Snow, Ernest Tubb and Mac Wiseman recording his songs throughout the 1950s for singles and albums. But it was the writer’s own versions of the songs that hold the greatest interest. He wrote and recorded some of the finest country weepers of all time, and it’s sad that outstanding songs like I Couldn’t Keep From Crying, The Same Two Lips, A Castle In The Sky and After You Leave are now forgotten, a part of the past and lost in their obscurity.

Many of Marty’s old songs would fit into today’s styling quite comfortably. This has been proved by several of his songs that have been recorded in recent years, some were in fact written more than twenty years ago. Johnny Cash recorded Kate and took it into the country charts only a few years ago, yet Marty wrote the song way back in 1954. Marty himself waited more than twenty years to record I’ve Got A Woman’s Love.

“I wrote I’ve Got A Woman’s Love in 1949. At the time I remember I was driving an old car and saw some people working on a farm in very hot weather. The sun was beating down on them and that little scene gave me the idea for the song. I thought it was just right for Frankie Laine. I sent it off to him also to other singers, I remember sending it to Rex Allen and Tennessee Ernie, but no one recorded it.”

Eventually Marty cut the song himself in 1970 for the MY WOMAN, MY WOMAN, MY WIFE LP. It was his most intrinsic album, centred around that universal panacea, love, in its most simplistic form. The album overreached everything that Marty had striven for in the past, and I feel it is necessary to be in the same state of mind as he was when he recorded it, to fully appreciate the quality and emotion.

It was his first recording following his serious heart operation when it was feared he might not pull through. The strength and support of his wife and two children gave Marty the necessary will to live that pulled him through. The album in some small way repays the love and devotion of those near to him.

When Robbins sings of love you know that someone, somewhere is the object of those affections. Nothing is contrived and everything comes from personal experience. My Woman, My Woman, My Wife won Marty the much coveted Grammy Award for best Country Song of 1971. It was a much deserved accolade for a song that meant a lot to Marty personally. It has since become a standard country and pop song, very popular with request shows.

All of Marty’s songs come either from his own experiences or those of others who have confided in him. He wrote Devil Woman in a small club in Nashville where he used to go in the wee small hours of the morning. He’d play the piano and write while the caretaker would be tidying up the place.

Franklin, Tennessee was written about a guy who left his home in Tennessee and headed for the West Coast determined to make his fortune. Marty met such a person working in a bar in San Francisco, broke and too proud to return home.

Although Marty Robbins is still signed to Acuff-Rose as a writer, he also owns his own music publishing firms which are all affiliated to Acuff-Rose. Naturally a lot of the material he records comes from the writers signed to these publishing firms and amongst the writers he has helped during his career are Tompall and Jim Glaser, Joe and Carol Babcock and Lee Emerson.

Marty explains how he operates his publishing interests: “Too many publishing firms sign up a young, green writer and tie him to a contract that gives him very little return on his songs. All of the writers who sign with me are free to go when they please. I’m only there to help them get a foot in the door.”

The problems a young writer can experience in Nashville was neatly summed up in Marty’s stunning Georgia Blood. Initially it was to have been included, along with Green Green Grass Of Home, Seventeen Years and The Chair on an album of prison songs which didn’t materialise. It tells of a new writer who moved from Georgia to Nashville, became involved with a crooked publisher and found his songs on the charts but no royalties forthcoming. Eventually the youngster lost his head, killed the crooked publisher and ended up in prison. Although events do not usually reach those sort of proportions, there is no doubt that many aspiring writers do get ripped off, and it would appear that Marty feels rather strongly about it. You will find the song on Marty’s GOOD ‘N’ COUNTRY LP.

Another song intended for the album of prison songs was I Did What I Did For Maria, which Marty originally recorded in the summer of 1972. The song written by Mitch Murray and an international hit for Tony Christie, eventually turned up on the EL PASO CITY LP in the spring of 1976. It is highly likely that Marty re-recorded the song, as he was signed to MCA Records from the end of 1972 through to mid 1975, although it appears that the recordings made for MCA do belong to Marty and could probably revert to American Columbia at some point.

Marty obviously had some problems during the early 1970s with Columbia which led to him signing with MCA. “I certainly was not happy”, he stated. “I couldn’t get the records out I wanted and they were very slow in promoting them. I was just like a small fish in a big pond and it seemed like a good time to move on. As it happened I feel that I wasted two years of my career at MCA. I was experimenting, trying to find a direction. Now I’m back home where I belong with Columbia and I feel we’ve both learnt a lot from my leaving.”

Certainly Marty came back strongly with Columbia, his first record since re-signing was with the controversial El Paso City, which took him back to the top of the cCountry charts. “It was a song I wrote on an airplane, it sort of came to me in a dream and I felt compelled to write it,” Marty continued, “I never thought it would be such a big hit, but I’m rather grateful it is.”

During the past two years Marty has recorded three new albums, all of them different, and all produced by Billy Sherrill. At times he is as middle-of-the-road as they come—as easy-listening as Englebert Humperdink or Des O’Connor, even, but somehow he escapes that trap of smugness which plagues that genre.

Robbins’ real strength is that he understands the mechanics of vocalising and his phrasing, while superficially unassuming, is quite adventurous. His choice of material underlines his good taste—Linda Hargrove’s I’ve Never Loved Anyone More, Bobby Darin’s Eighteen Yellow Roses and Jean Chapel’s To Get To You interspersed with his own low-keyed compositions.

Don’t Let Me Touch You and Falling Out Of Love are very successful at showing he can still write beautifully and commercially. The way he can add emotion to his already rich voice without going over the top is a lesson to all.

Since re-signing with Columbia it would appear that Marty has several songs in the ‘can’ not yet released. He spoke in 1976 about John Denver’s Back Home Again and Take Me Home Country Roads plus Rhinestone Cowboy being included on the EL PASO CITY album, but to date they have not appeared. When his contract with MCA expired Marty had enough material for another album and some of the songs that were mentioned were To Get To You, Among My Souvenirs and I’m Kin To The Wind. These three songs have since appeared on his Columbia albums, whether they are re-recordings is not known. Certainly Jean Chapel’s To Get To You has the same styling of most of the tracks on Marty’s second MCA album.

This is not the first time that songs Marty has recorded have not appeared for several years. In the summer of 1971 he was planning an album to be titled FAST CARS AND PRETTY GIRLS. Among the songs written for this were Twentieth Century Drifter and Martha, both of which later appeared on MCA albums. The follow-up album to MY WOMAN, MY WOMAN, MY WIFE was due to be a sacred album and though he recorded several songs like, Father, It Was Worth It All and A Little Spot In Heaven, the project was scrapped because Marty was not entirely happy with the results.

A recording perfectionist, Marty Robbins is one of the most admired vocalists in country music. While the base of his work lies in country music his songs are coloured with many traces of Spanish, Mexican and Hawaiian influences. The most significant quality about his vocal work is the expressiveness in feeling. It’s a trait that puts the listener in a sort of trance as one marvels at the brilliance of the tones.

Marty Robbins! Here is a man who has been a successful country music star for more than twenty-five years. A top class singer, outstanding songwriter and brilliant entertainer whose talent seems to know no boundaries.

Marty Robbins! Here is a man who has been a successful country music star for more than twenty-five years. A top class singer, outstanding songwriter and brilliant entertainer whose talent seems to know no boundaries.It was Easter 1975 when he made his British debut at Wembley. He had put off coming to Britain on previous occasions because he hadn’t enjoyed any sort of chart success in years. He need never have worried. He does of course have an illustrious background and he went through many of his most famous songs like El Paso, Ribbon Of Darkness, Tonight Carmen and Devil Woman, all sung faultlessly and with a life and originality about his style of delivery that was absent from most of the other performers.

His reputation was greatly enhanced the following year by a return appearance at Wembley and a short concert tour which delighted his fans and introduced him to a lot of people who only vaguely knew of his work and never appreciated his high standard of entertaining.

His charismatic performances were a revelation, his vocal style and degree of control just a magical experience. Yet there has been a lot of criticism of Marty’s record releases of late by people who only wish him well, and could even be counted as ‘fans’—the words ‘similarity’ and even ‘boring’ have begun creeping in.

Robbins’ style is his greatness and obviously this is what he wishes to consolidate. Wisely he doesn’t let himself become burdened down or limited to a specific style. He could, if he so wished, follow so many of the other top country names and pad his albums up with the current hits, but Marty has never been one to follow trends.

Back in 1959 he went against the trend, writing and recording a string of cowboy ballads. In 1962 it was an Hawaiian flavoured song, Devil Woman, that brought him more international success. Three years later he jumped the gun again and was the first country artist to record a Gordon Lightfoot song—Ribbon Of Darkness. It proved to be the beginning of folk-country, a style that launched Waylon Jennings, George Hamilton IV and Bobby Bare high into the country charts.

During Marty’s last British tour in April 1976, he took time out from a busy schedule to speak to me at length about his career, plans for the future and the material that he has recorded down through the years. Like so many recording artists, Marty is inundated with songs from aspiring writers. With more than three hundred of his own songs to his credit, Marty can, naturally, be choosy as to what he records.

“All too often songwriters will send me Marty Robbins’ type songs. I don’t need them, I can write those myself. I’m always on the look out for songs that are different,” Marty explains. “This is how I came to record Singing The Blues. It was submitted by Melvyn Endsley, a very talented writer. At the time I remember him playing all these sad ballads which were in the style I had back in the early fifties, then suddenly there was this song that was completely different. It was Singing The Blues and I was really enthusiastic about it.”

Even today it is amazing the number of people who think that either Singing The Blues, A White Sport Coat or El Paso were Marty’s first recordings. But you must go back a bit further to 1952 for Marty’s initial work. In fact, before Singing The Blues was released in the autumn of 1956, Marty had released twenty-two singles.

They illustrated the ultimate in pure country music. Most of the songs like I’ll Go On Alone, Sing Me Something Sentimental, Love Me Or Leave Me Alone and Pretty Words being written by the singer. There was a central theme in his writing for most of those singles which has since been diffused into a pot-pourri of themes and styles.

One of country music’s most effective writers, Marty not only dwells on the beauties of approval, but also examines the sadness and lack of confidence that results when one experiences rejection. He sings of broken romance as his loved one leaves in Tomorrow You’ll Be Gone, a simple piece of lyrical poetry backed up by beautiful steel guitar that seems to cry with Robbins as he pours his heart out. It was one of the finest debut records of the time.

I asked Marty about these early recordings, which were mainly recorded in Dallas, Texas. How did he feel about their apparent rejection by the country fans at the time.

His reply showed how little we fully understand the American country music scene of the mid-1950s. “Well, to me at the time, I was successful. I was singing and playing my own songs, and though they didn’t exactly top the charts, it certainly didn’t worry me. I was just so happy to be recording and appearing in front of audiences for a living.”

Marty’s talent at the time certainly didn’t go unnoticed. The late Fred Rose flew out to Phoenix to sign him as a writer with Acuff-Rose towards the end of 1951 and this proved to be one of their best investments. “I was really proud to be signed up by Fred Rose. He taught me a lot about the ethics of being a songwriter. In the early days, several of the big stars, you know, I can’t name them, offered to record my songs if I would give them a share of the song. There’s no way I would do that. They were my songs, a part of my life, and I certainly was not prepared to give any of that away.”

But Marty’s songs did get recorded with Webb Price recording I’ll Go On Alone and other stars like Hank Snow, Ernest Tubb and Mac Wiseman recording his songs throughout the 1950s for singles and albums. But it was the writer’s own versions of the songs that hold the greatest interest. He wrote and recorded some of the finest country weepers of all time, and it’s sad that outstanding songs like I Couldn’t Keep From Crying, The Same Two Lips, A Castle In The Sky and After You Leave are now forgotten, a part of the past and lost in their obscurity.

Many of Marty’s old songs would fit into today’s styling quite comfortably. This has been proved by several of his songs that have been recorded in recent years, some were in fact written more than twenty years ago. Johnny Cash recorded Kate and took it into the country charts only a few years ago, yet Marty wrote the song way back in 1954. Marty himself waited more than twenty years to record I’ve Got A Woman’s Love.

“I wrote I’ve Got A Woman’s Love in 1949. At the time I remember I was driving an old car and saw some people working on a farm in very hot weather. The sun was beating down on them and that little scene gave me the idea for the song. I thought it was just right for Frankie Laine. I sent it off to him also to other singers, I remember sending it to Rex Allen and Tennessee Ernie, but no one recorded it.”

Eventually Marty cut the song himself in 1970 for the MY WOMAN, MY WOMAN, MY WIFE LP. It was his most intrinsic album, centred around that universal panacea, love, in its most simplistic form. The album overreached everything that Marty had striven for in the past, and I feel it is necessary to be in the same state of mind as he was when he recorded it, to fully appreciate the quality and emotion.

It was his first recording following his serious heart operation when it was feared he might not pull through. The strength and support of his wife and two children gave Marty the necessary will to live that pulled him through. The album in some small way repays the love and devotion of those near to him.

When Robbins sings of love you know that someone, somewhere is the object of those affections. Nothing is contrived and everything comes from personal experience. My Woman, My Woman, My Wife won Marty the much coveted Grammy Award for best Country Song of 1971. It was a much deserved accolade for a song that meant a lot to Marty personally. It has since become a standard country and pop song, very popular with request shows.

All of Marty’s songs come either from his own experiences or those of others who have confided in him. He wrote Devil Woman in a small club in Nashville where he used to go in the wee small hours of the morning. He’d play the piano and write while the caretaker would be tidying up the place.

Franklin, Tennessee was written about a guy who left his home in Tennessee and headed for the West Coast determined to make his fortune. Marty met such a person working in a bar in San Francisco, broke and too proud to return home.

Although Marty Robbins is still signed to Acuff-Rose as a writer, he also owns his own music publishing firms which are all affiliated to Acuff-Rose. Naturally a lot of the material he records comes from the writers signed to these publishing firms and amongst the writers he has helped during his career are Tompall and Jim Glaser, Joe and Carol Babcock and Lee Emerson.

Marty explains how he operates his publishing interests: “Too many publishing firms sign up a young, green writer and tie him to a contract that gives him very little return on his songs. All of the writers who sign with me are free to go when they please. I’m only there to help them get a foot in the door.”

The problems a young writer can experience in Nashville was neatly summed up in Marty’s stunning Georgia Blood. Initially it was to have been included, along with Green Green Grass Of Home, Seventeen Years and The Chair on an album of prison songs which didn’t materialise. It tells of a new writer who moved from Georgia to Nashville, became involved with a crooked publisher and found his songs on the charts but no royalties forthcoming. Eventually the youngster lost his head, killed the crooked publisher and ended up in prison. Although events do not usually reach those sort of proportions, there is no doubt that many aspiring writers do get ripped off, and it would appear that Marty feels rather strongly about it. You will find the song on Marty’s GOOD ‘N’ COUNTRY LP.

Another song intended for the album of prison songs was I Did What I Did For Maria, which Marty originally recorded in the summer of 1972. The song written by Mitch Murray and an international hit for Tony Christie, eventually turned up on the EL PASO CITY LP in the spring of 1976. It is highly likely that Marty re-recorded the song, as he was signed to MCA Records from the end of 1972 through to mid 1975, although it appears that the recordings made for MCA do belong to Marty and could probably revert to American Columbia at some point.

Marty obviously had some problems during the early 1970s with Columbia which led to him signing with MCA. “I certainly was not happy”, he stated. “I couldn’t get the records out I wanted and they were very slow in promoting them. I was just like a small fish in a big pond and it seemed like a good time to move on. As it happened I feel that I wasted two years of my career at MCA. I was experimenting, trying to find a direction. Now I’m back home where I belong with Columbia and I feel we’ve both learnt a lot from my leaving.”

Certainly Marty came back strongly with Columbia, his first record since re-signing was with the controversial El Paso City, which took him back to the top of the cCountry charts. “It was a song I wrote on an airplane, it sort of came to me in a dream and I felt compelled to write it,” Marty continued, “I never thought it would be such a big hit, but I’m rather grateful it is.”

During the past two years Marty has recorded three new albums, all of them different, and all produced by Billy Sherrill. At times he is as middle-of-the-road as they come—as easy-listening as Englebert Humperdink or Des O’Connor, even, but somehow he escapes that trap of smugness which plagues that genre.

Robbins’ real strength is that he understands the mechanics of vocalising and his phrasing, while superficially unassuming, is quite adventurous. His choice of material underlines his good taste—Linda Hargrove’s I’ve Never Loved Anyone More, Bobby Darin’s Eighteen Yellow Roses and Jean Chapel’s To Get To You interspersed with his own low-keyed compositions.

Don’t Let Me Touch You and Falling Out Of Love are very successful at showing he can still write beautifully and commercially. The way he can add emotion to his already rich voice without going over the top is a lesson to all.

Since re-signing with Columbia it would appear that Marty has several songs in the ‘can’ not yet released. He spoke in 1976 about John Denver’s Back Home Again and Take Me Home Country Roads plus Rhinestone Cowboy being included on the EL PASO CITY album, but to date they have not appeared. When his contract with MCA expired Marty had enough material for another album and some of the songs that were mentioned were To Get To You, Among My Souvenirs and I’m Kin To The Wind. These three songs have since appeared on his Columbia albums, whether they are re-recordings is not known. Certainly Jean Chapel’s To Get To You has the same styling of most of the tracks on Marty’s second MCA album.

This is not the first time that songs Marty has recorded have not appeared for several years. In the summer of 1971 he was planning an album to be titled FAST CARS AND PRETTY GIRLS. Among the songs written for this were Twentieth Century Drifter and Martha, both of which later appeared on MCA albums. The follow-up album to MY WOMAN, MY WOMAN, MY WIFE was due to be a sacred album and though he recorded several songs like, Father, It Was Worth It All and A Little Spot In Heaven, the project was scrapped because Marty was not entirely happy with the results.

A recording perfectionist, Marty Robbins is one of the most admired vocalists in country music. While the base of his work lies in country music his songs are coloured with many traces of Spanish, Mexican and Hawaiian influences. The most significant quality about his vocal work is the expressiveness in feeling. It’s a trait that puts the listener in a sort of trance as one marvels at the brilliance of the tones.