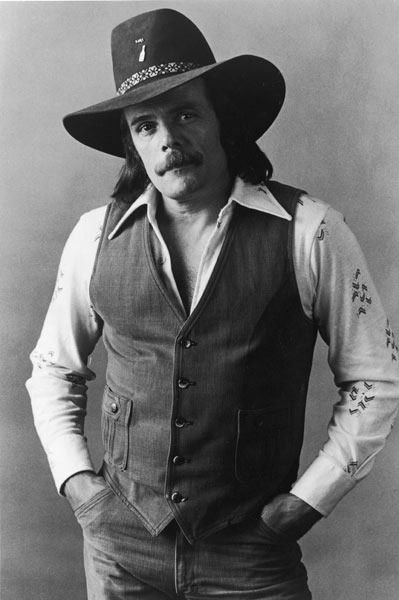

Johnny Paycheck

A one-time Nashville renegade, Johnny Paycheck was an ‘Outlaw’ before Waylon and Willie had even thought about leaving Texas. It took more than twenty years of hard-drinking, womanising, pill-popping and near-misses before Paycheck finally made the breakthrough to commercial success in the late 1970s. The man who stood up for the working man and proudly proclaimed across American jukeboxes to Take This Job And Show It, finally screwed up one time too many. He followed that 1977 smash with a rapid and painful downfall back into alcoholism and drugs, bankrupcy, a rock-bottom reputation and a serious assault related to a barroom shooting incident that resulted in a nine-year prison sentence. An early publicity handout, written before much of that had even taken place, stated: ‘With a life story that fits impeccably into the rags-to-riches-to-rags-to-riches stereotype, the only truly amazing thing about Johnny Paycheck is that no one has yet seen fit to put his biography on the silver screen. Change a couple of names to protect the guilty and avoid lawsuits and you’d have an instant smash.’ The only problem, of course, is that very few would ever have believed a word of it.

A one-time Nashville renegade, Johnny Paycheck was an ‘Outlaw’ before Waylon and Willie had even thought about leaving Texas. It took more than twenty years of hard-drinking, womanising, pill-popping and near-misses before Paycheck finally made the breakthrough to commercial success in the late 1970s. The man who stood up for the working man and proudly proclaimed across American jukeboxes to Take This Job And Show It, finally screwed up one time too many. He followed that 1977 smash with a rapid and painful downfall back into alcoholism and drugs, bankrupcy, a rock-bottom reputation and a serious assault related to a barroom shooting incident that resulted in a nine-year prison sentence. An early publicity handout, written before much of that had even taken place, stated: ‘With a life story that fits impeccably into the rags-to-riches-to-rags-to-riches stereotype, the only truly amazing thing about Johnny Paycheck is that no one has yet seen fit to put his biography on the silver screen. Change a couple of names to protect the guilty and avoid lawsuits and you’d have an instant smash.’ The only problem, of course, is that very few would ever have believed a word of it. Born Donald Lytle on May 31, 1937 in Greenfield, Ohio, he was performing in talent contests by the age of nine, and riding the rails as a drifter by the time he turned fifteen, performing in bars and clubs as the ‘Ohio Kid.’ He joined the Navy and following a fight with an officer, ended up in the brig for two years. After his discharge, he arrived in Nashville and under the tutelage of Buddy Killen, he recorded for Decca and Mercury using the name Donny Young. In between the recordings he went to work for some of the top bands in country music including those of Porter Wagoner, Ray Price and Faron Young. He started on the road with George Jones’ band in 1960, playing bass and singing high harmonies on at least 15 albums and such hits as The Race Is On and Love Bug. It was a love-hate relationship, both being highly volatile and heavily into booze and drugs. Paycheck’s vocal influence on Jones (and later Merle Haggard) went unaccredited for decades but in recent years has been more widely acknowledged.

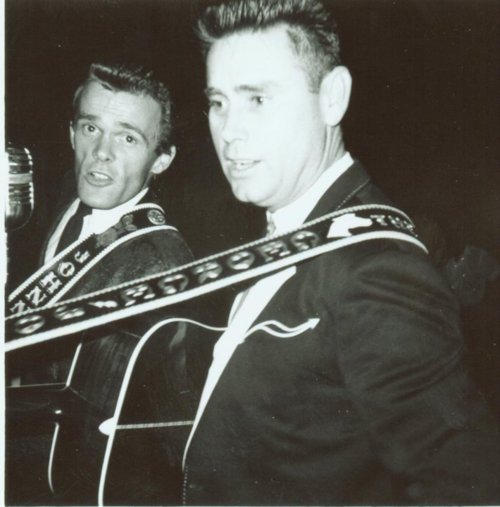

Born Donald Lytle on May 31, 1937 in Greenfield, Ohio, he was performing in talent contests by the age of nine, and riding the rails as a drifter by the time he turned fifteen, performing in bars and clubs as the ‘Ohio Kid.’ He joined the Navy and following a fight with an officer, ended up in the brig for two years. After his discharge, he arrived in Nashville and under the tutelage of Buddy Killen, he recorded for Decca and Mercury using the name Donny Young. In between the recordings he went to work for some of the top bands in country music including those of Porter Wagoner, Ray Price and Faron Young. He started on the road with George Jones’ band in 1960, playing bass and singing high harmonies on at least 15 albums and such hits as The Race Is On and Love Bug. It was a love-hate relationship, both being highly volatile and heavily into booze and drugs. Paycheck’s vocal influence on Jones (and later Merle Haggard) went unaccredited for decades but in recent years has been more widely acknowledged.In 1965 he renamed himself Johnny Paycheck (from John Austin Paycheck, a Chicago prize fighter) and working with producer Aubrey Mayhew charted with a couple of minor country hits A-11 and Heartbreak Tennessee. The following year, he and Mayhew started Little Darlin’ Records. The Lovin’ Machine, a celebration of the automobile, became his first top 10 hit and that was followed by more classic recordings that embraced a series of strange characters and soap opera storylines through such oddly titled songs as (Pardon Me) I’ve Got Someone To Kill, He’s In A Hurry (To Get Home To My Wife), Don’t Monkey With Another Monkey’s Monkey and If I’m Gonna Sink (I Might As Well Go To The Bottom).

The Little Darlin’ recordings were all stone country, honky-tonk, driven by Paycheck’s keening hillbilly vocals and the superb steel guitar work of a young Lloyd Green. In a just world, they would all have been big-sellers. They certainly stood out at a time when string-laden pop-country ruled the airwaves. It was around this time that Paycheck also made the grade as a songwriter, his Apartment No. 9 affording Tammy Wynette her first hit. Touch My Heart, another of his compositions, providing Ray Price with a top 10 hit.

Little Darlin’ folded at the end of the 1960s and Paycheck and Mayhew split up—the break drove the singer into a two-year drug and alcohol fuelled exile somewhere in California. It was legendary Nashville producer Billy Sherrill who resurrected Paycheck’s career in 1971 with the back-to-back hits She’s All I Got and Someone To Give My Love To and shepherded him as a mainstay of the CBS Records Nashville roster. Renowned for his lush, countrypolitan arrangements, Sherrill never could quite polish up Paycheck’s rough edges, so though these recordings were not as wild or uninhibited as the Little Darlin’ sides, they still retained a tense, soulfulness that lifted them way above the Nashville norm.

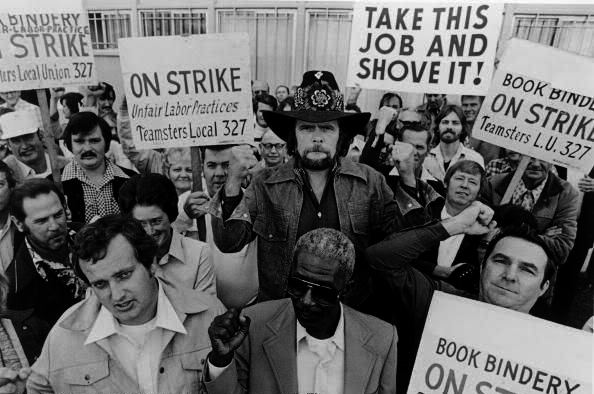

For the next few years he was hardly out of the charts and finally Paycheck was becoming a star. Though he appeared to be off the booze, his wild ways had not changed all that much. He was convicted of cheque forgery and in 1976, was saddled with a paternity suit, tax problems, and bankrupcy. After a couple of lean years on the charts, he bounced back with a harder-edged sound and image. 1976’s 11 Months And 29 Days, (which happened to be the length of his suspended sentence for passing a bad cheque), featured a photo of him in a jail cell on the cover. He notched up three major hit singles with Slide Off Your Satin Sheets, I’m the Only Hell (Mama Ever Raised) and Take This Job And Shove It. The latter, one of David Allan Coe’s anti-establishment anthems, became one of the year’s biggest sellers. Paycheck’s records were like parodies of his lifestyle, as the titles Me And The I.R.S. and D.O.A. (Drunk On Arrival) indicated. His unruly behaviour once again had an impact on his chart success. A flight attendant sued him for slander after he began a fight on a plane and he was arrested for alleged rape (the charges were later reduced). By 1982 Epic had had enough and dropped him from the label.

He moved over to AMI, where he had a number of small hit singles between 1984 and 1985. Then came that infamous bar-room brawl with a complete stranger in Hillsboro, Ohio, that ended with Paycheck shooting and injuring his opponent. While appealing his nine-year prison sentence for aggravated assault, he recorded for Mercury Records, making the top twenty with Old Violin in 1986.

Despite the fact that he became a born-again Christian around 1988, the appeals ran out the following year and Paycheck was sent to the Chillicothe Correctional Institute in 1989. He spent two years behind bars and even got to perform a prison concert with Merle Haggard, before being released on parole in January 1991. Known for years as a renegade and victim of drugs and booze, Paycheck came out of prison clean. He also made good on the conditions of his parole. He kept his life on a straight course and gave anti-drug talks to young kids around the country as part of his required community service. To his credit, and with an uphill battle ahead of him, the singer returned to the music industry and tried to once again resurrect his career. The singer resumed his touring career, which included appearances in Branson, Missouri, and recorded for Playback Records. In 1996, the Country Music Foundation released a collection of Paycheck’s early recordings for Little Darlin’ that found favour with young fans of classic country music. In 1997 he became a member of the Grand Ole Opry and in 1999 he recorded a live album at Gilley’s, released on Atlantic.

He began to suffer with poor health mainly based around asthma and emphysema. In January 1998 he was airlifted to hospital in Albuquerque, New Mexico after suffering a severe asthma attack. He had recently signed with Sony Music Nashville imprint Lucky Dog Records. Blake Chancey was due to produce the new Paycheck album, but continuing ill-health put the project on hold.

It appeared as if Johnny Paycheck had beaten his demons during the final years of his life. He never shrunk from the bad-boy reputation that he had created, but he professed to more than a decade of sobriety. But even as his credibility rose, his health was deteriorating. Breathing problems repeatedly sent him to the hospital during his last few years, and he was unable to rally from emphysema. His final contribution as a performer was on Daryle Singletary’s THAT’S WHY I SING THIS WAY album. Singletary re-recorded his Old Violin and invited the old outlaw to supply the song’s recitation, which he recorded from his bed. Just a few weeks later, Johnny Paycheck died in his sleep on February 18, 2003.

Specialising in dark heartbreaking songs, Paycheck examined the possibility of his own death—a death caused by heartache—in a 1960s recording called The Late And Great Me. ‘All my friends are dressed in black and they’re standing reverently/Let’s have a few moments silence for the late and great me.’

There was never anything phoney about Paycheck’s music. He was one of those rare artists that wouldn’t sing it if he didn't feel it and acknowledged that much of his work was reflective of the life he lived. ‘That was me, them’s all life,’ he said a year before he passed away, ‘I regret a lot of that stuff I did.’ All too often Paycheck’s headline making exploits have over-shadowed his musical achievements. It is a great pity, for it just so happens that he was one of the mightiest honky-tonk singers of his era.

He left a colourful legacy with some ace honky-tonk recordings. The ‘outlaw’ label he earned always transcended his legal troubles. ‘To me, an outlaw is a man that did things his own way, whether you liked him or not,’ he once said. ‘This world is full of people that want you to do things their way, not necessarily the way you want to do it. I did things my way.’

You’ll hear Paycheck at his finest with his impeccable rendition of Jerry Jeff Walker’s Mr Bojangles—you definitely feel that here was a man who’d sat in that prison cell with the destitute dancer. Realism was always the name of the game with Paycheck—grit, honesty and integrity despite the production overkill.

Recommended Listening

Jukebox Charlie (Little Darlin’ 1967)

Somebody Loves Me (Epic 1973)

Take This Job And Shove It (Epic 1978)

Armed & Crazy (Epic 1979)

Everybody’s Got A Family … Meet Mine (Epic 1980)

The Real Mr. Heartache (Country Music Foundation 1996)

Johnny Paycheck aka Donny Young: Shakin’ The Blues

(Bear Family 2006)

The Soul & The Edge: The Best Of Johnny Paycheck

(Epic/Legacy 2002)

Someone To Give My Love To/Somebody Loves Me

(Hux Records 2010)

Various Artists Touch My Heart: A Tribute to Johnny Paycheck (Sugar Hill 2004)