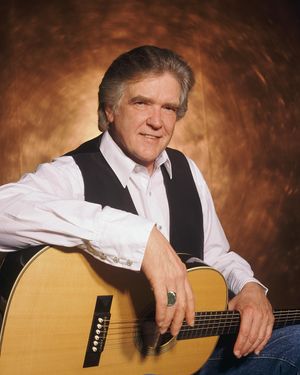

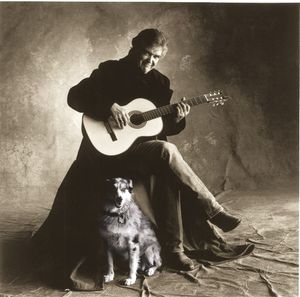

Guy Clark Obituary

Guy Clark, probably the greatest singer-songwriter of my generation, passed away on May 17, 2016. He was 74. The Texas-born troubadour had been battling failing health for some time, yet still continued writing songs, recording and playing his trusty home made guitars. Guy Clark was the very personification of the Texas songwriting tradition. Long revered as a writer of assured perception and considerable insight, his enduring stature was solidified on the strength of quality songs like Desperados Waiting For A Train, L.A Freeway, That Old Time Feeling and Texas, 1947. Early on in his career he became better known for his songs than his own recordings, and over the years he watched as some of American music’s most respected artists covered his songs, including Ricky Skaggs (Heartbroke), Johnny Cash (Let Him Roll), Jerry Jeff Walker (Like A Coat From The Cold), Bobby Bare (New Cut Road), and Rodney Crowell (She’s Crazy For Leaving). These interpretative tributes more than made up for the superstardom that Guy never really craved anyway. Just earning a living making music had really always been Guy’s goal and ambition in life as he told me several years ago. “I just knew that I would be doing it as long as I lived. I didn’t want to have to do something else. I wanted to pay for myself and you know, shit, I wouldn’t mind being rich. I had always intended to make a living out of it.”

Guy Clark, probably the greatest singer-songwriter of my generation, passed away on May 17, 2016. He was 74. The Texas-born troubadour had been battling failing health for some time, yet still continued writing songs, recording and playing his trusty home made guitars. Guy Clark was the very personification of the Texas songwriting tradition. Long revered as a writer of assured perception and considerable insight, his enduring stature was solidified on the strength of quality songs like Desperados Waiting For A Train, L.A Freeway, That Old Time Feeling and Texas, 1947. Early on in his career he became better known for his songs than his own recordings, and over the years he watched as some of American music’s most respected artists covered his songs, including Ricky Skaggs (Heartbroke), Johnny Cash (Let Him Roll), Jerry Jeff Walker (Like A Coat From The Cold), Bobby Bare (New Cut Road), and Rodney Crowell (She’s Crazy For Leaving). These interpretative tributes more than made up for the superstardom that Guy never really craved anyway. Just earning a living making music had really always been Guy’s goal and ambition in life as he told me several years ago. “I just knew that I would be doing it as long as I lived. I didn’t want to have to do something else. I wanted to pay for myself and you know, shit, I wouldn’t mind being rich. I had always intended to make a living out of it.”Over the years I interviewed Guy on many occasions. Sometimes he could be a little abrasive, especially so when he’d been on tour in the UK and was either suffering from jet-lag or had just about tolerated a long, tiring trip down from Scotland to London. But most times I found him courteous, in that old-fashioned Texas way, funny when the moment took him and very passionate about his obvious love of music and fellow writers and musicians.

It was back in 1975 that I first got to talk to Guy shortly after the release of OLD NO. 1, his groundbreaking debut album released on RCA. It was, and remains the pinnacle of contemporary or progressive country music of the 1970s and flew in the face of the smooth pop-country crossovers of the likes of Charlie Rich, John Denver, BJ Thomas and Tanya Tucker.

He created his own sound with a firm imagistic grip and off-hand lyrical grace. His vocals had an immediate conversational quality. The songs were mostly populated by carefully conceived portraits of losers, drifters and loners (preoccupations which continued to dominate his work for the next 40 years) drawn from the Texas landscape, and ranging from the emotionally enthralling That Old Time Feeling (‘that old time feelin’ rocks and spits and cries/like an old lover rememberin’ the girl with the clear blue eyes’) to the more raucous barroom roller of Rita Ballou and the wryly tender She Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere. LA Freeway found him, like Sam Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner, waving ‘adios to all this concrete’ and setting out into another desert sunset.

This style was most forcefully evident on Texas, 1947 based specifically on an incident from his childhood in Monahans—the classic Desperados Waiting For The Train and the painfully elegaic Let Him Roll, about the death and funeral of an old cowboy forced into alcoholism and despair by the passing of time and his unrequited love for a Dallas whore.

This latter song, especially, with its discreetly contrived atmosphere and attention to detail, recalled the romantic cinema of John Ford: indeed, this trio of songs contained a breadth of incident and detail that was positively cinematic in range and construction. Even better, if this was not enough, was Instant Coffee Blues, a carefully observed composition that related the chance encounter of a truck driver and a truck-stop waitress. The depressing loneliness of their lives was captured with economy and skill as Clark described their painful inability to exchange even one word as they inevitably part the next morning, eager to erase the memory of their night together.

I’ve lived with the OLD NO 1 album for 40 years. For me it’s the benchmark of all that is great in country music songwriting. If Guy Clark had never written another song or recorded any more albums, I believe that he would still deserve to be regarded as legendary. But over the years he did continue to write and record. There’s been some 14 subsequent albums, each one a minor classic in its own right, a body of original songs second to none.

I’ve lived with the OLD NO 1 album for 40 years. For me it’s the benchmark of all that is great in country music songwriting. If Guy Clark had never written another song or recorded any more albums, I believe that he would still deserve to be regarded as legendary. But over the years he did continue to write and record. There’s been some 14 subsequent albums, each one a minor classic in its own right, a body of original songs second to none.Guy Charles Clark was born on November 6, 1941 in Monahans, Texas, and spent much of his early life living with his grandmother in a run-down hotel, which provided the inspiration for many of his later songs. His father, who fought in World War II and went on to obtain a law degree, would lead the family through dinnertime poetry readings at their new home in the coastal Texas town of Rockport, making sure his son learned to use what would become his most vital gift: his imagination. There were no television sets at home—Guy turned to literature instead and eventually sports, playing on multiple teams in high school while he learned the ropes of the guitar, an instrument which he would eventually not only master playing but learn to build. He studied not just traditional strumming but was enchanted by Mexican folk and flamenco, sounds that would often influence his own writing and playing.

In 1963, Guy joined the Peace Corps, and, after realising that he’d rather play music and delve much deeper into the folk tradition than attending college could ever offer him, he moved to Houston. He made a living repairing guitars and playing gigs around town at venues like Oak Water, Liberty Hall, the Jester Lounge and Sand Mountain—it was there he met fellow struggling songwriters and musicians Mickey Newbury, Townes Van Zandt, Jerry Jeff Walker, Kay Oslin (later known as KT Oslin), Frank Davis, Gary White and Crow Johnson. He married his first wife, folksinger Susan Spaw, and they had a son Travis in 1966.

Guy and Van Zandt became friends, colleagues and admirers of each other's work throughout their lifetime together, often known as the two most ardent poets of the Texas folk-country tradition: Lyle Lovett once described Clark as the prose-master to Van Zandt's poetry.

In 1969, after splitting with Susan, Guy moved to San Francisco and again worked in a guitar repair shop. Within a year, he moved back to Houston, met and fell in love with a beautiful dark-haired painter named Susanna Talley. Susanna moved from Oklahoma City to Houston to be with Guy and after a few months, she sold a painting to fund the couple’s move to Los Angeles. Guy found work building Dobros at the Dopyera Brothers Original Musical Instruments Company. He played with a bluegrass band on the weekends and pitched his songs to publishing companies in between.

Los Angeles wasn’t for him, as anyone listening to LA Freeway, a song written about his dissatisfaction with the hectic Californian lifestyle could detect: ‘if I could just get off of that LA freeway without getting killed or caught,’ he mused in the lyrics. By then his friends from Houston—an expanding circle including Van Zandt, Jerry Jeff Walker, Steve Earle, Billy Joe Shaver and Rodney Crowell—were all gravitating toward Nashville.

Los Angeles wasn’t for him, as anyone listening to LA Freeway, a song written about his dissatisfaction with the hectic Californian lifestyle could detect: ‘if I could just get off of that LA freeway without getting killed or caught,’ he mused in the lyrics. By then his friends from Houston—an expanding circle including Van Zandt, Jerry Jeff Walker, Steve Earle, Billy Joe Shaver and Rodney Crowell—were all gravitating toward Nashville.He signed a publishing deal with Sunbury Dunbar and in 1971 the couple decided to leave California and moved to Nashville so that Guy could pursue his songwriting career. They arrived in Nashville at a time when the popular image of country music was being wrestled from the bland embrace of the commercial and conservative establishment. Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, from within the establishment, and Gram Parsons, from without, had revitalised country forms, and re-introduced to the music an integrity that had been lost for too long.

Guy’s move to Music City, one of three cities where Sunbury had offices and where his pal Mickey Newbury would make him welcome, proved fortuitous. The Clark’s East Nashville home became a Mecca for aspiring songwriters, with youngsters like Steve Earle, Rodney Crowell all hanging out there with the more established Newbury, Van Zandt, Billy Joe Shaver, Dave Loggins and David Allan Coe. Guy and his wife, Susanna, would become the axis for this groundbreaking fraternity of singer-songwriters for whom Nashville felt like ‘Paris in the 1920s.’

Bonded by their egalitarianism, the troupe’s favoured sidewalk cafe was the Clark’s dining room table, where they gathered frequently for ‘guitar pulls’ and show-and-tell song swapping sessions, and where they celebrated their successes and facetiously threatened to kill whoever had presented the best new song. Susanna Clark, a talented painter, tossed her brushes aside for a while, joined the invasion and began writing hit songs herself.

In 1972 country-folk singer-songwriter Jerry Jeff Walker, then newly ensconced in Austin, released an eponymous album featuring the Clark composition LA Freeway, which became an FM radio hit. In 1973, Walker released VIVA! TERLINGUA, recorded live in a Texas dance hall and including Guy’s ballad Desperados Waiting For A Train. As much as any others, these two Clark songs may arguably be said to have set the tone for a musical revolution that was first known as progressive country. By 1975, many of the revolutionaries would be defined as the Outlaws. Like the Bakersfield sound of the 1960s, the new sounds were a reaction to the formulaic rigidity and paternalism of Nashville’s record producers and label executives.

In this alternative musical world of the early 1970s, inspired by the storytelling poems of Robert Frost and Stephen Vincent Benet, Guy began to write what he knew ‘with a pencil and a big eraser.’ Like almost all his songs, these two early masterpieces were expressions of personal memory and experience, further characterised by words that have a melody all their own.

Soon more artists began recording Guy’s, songs including Johnny Cash (Texas 1947, The Last Gunfighter Ballad), David Allan Coe (Desperados Waiting For A Train) and the Everly Brothers (A Nickel For the Fiddler). Signed to RCA Records, he recorded an album in 1973, but scrapped it due to personal dissatisfaction. A return to the studio in late 1974 resulted in the OLD NO. 1 album, which was critically acclaimed, but failed to make a commercial impact. A second album, TEXAS COOKIN’, was equally impressive, but even with guest appearances by Waylon Jennings, Emmylou Harris, Rodney Crowell and Hoyt Axton, failed to provide any hit singles.

Frustrated by RCA’s seemingly inability to capitalise on his songwriting successes, he ended his contract with the label with some bitterness and regret and in 1978 joined Warner Bros. Records. During the next five years he recorded three more superb albums and also made brief appearances on the country charts with The Partner Nobody Chose (1981) and Homegrown Tomatoes (1983). Following a four-year recording hiatus, he was back in the studio to make OLD FRIENDS, for Sugar Hill, which was picked up for European release on U2’s Mother Records. This led to several European trips, where his intimate solo shows gained him a cult following among young music fans.

In 1982, famed song-smith Bobby Bare made it to the country top twenty with Guy’s New Cut Road. That same year, bluegrass icon Ricky Skaggs escalated his mainstream trajectory with Guy’s Heartbroke, a number one song that permanently established Clark’s reputation as an ingenious songwriter. Among the many others who scored hits with Guy Clark songs during this period are Vince Gill, who took Oklahoma Borderline to the top ten in 1985; the Highwaymen, who introduced Desperados Waiting For A Train to a new generation that same year; and John Conlee, whose interpretation of The Carpenter made the top ten in 1987. Steve Wariner reached the top five with Baby I’m Yours in 1988, and the same year Asleep at the Wheel charted with Blowin’ Like A Bandit. Crowell was Clark’s co-writer on She’s Crazy For Leavin’, which in 1989 became the third of five straight number one hits for Crowell.

Guy was signed to Asylum’s American Explorer label for 1992’s BOATS TO BUILD and 1995’s DUBLIN BLUES, then returned to Sugar Hill for 1997’s KEEPERS—A LIVE RECORDING, and 1999’s COLD DOG SOUP. Later in life, he would embrace co-writes more frequently, enjoying collaborations with modern country writers such as Roger Murrah, Jim McBride, Lee Roy Parnell, Vince Gill, Shawn Camp, Hank DeVito, Darrell Scott, Gary Nicholson, plus the lesser-known (but equally talented) Steve Nelson, Ray Stephenson, Verlon Thompson and BR549’s Chuck Mead.

He released one more album, THE DARK, for Sugar Hill in 2002, before he moved across to Dualtone for WORKBENCH SONGS four years later. It was around this time that he was diagnosed with lymphoma, but he battled the illness with the same stern, true countenance he employed onstage and continued with his songwriting and recordings, releasing three more albums for Dualtone. 2013’s MY FAVORITE PICTURE OF YOU, his final album, won a Grammy Award for Best Folk Album. In it, he told of a particular photograph of his beloved wife, Susanna, who had passed away the year prior from lung cancer: ‘my favourite picture of you is the one where your wings are showing,’ he sung in his warm, ragged coo. As always, he could see what both was and wasn’t there with the clearest of vision.

By then, his past struggle with cancer had ravaged his system as had the toll of hard living—equally so the death of his wife. His touring life, though once strong and vital, had slowed down, and he had taken to walking with a cane, but he still frequently invited friends and collaborators down into his basement studio to write, smoke cigarettes and play guitar, even though he was no longer able to stand long enough to craft the instruments himself. On the wall, hung the photo of Susana that inspired those last songs: her arms crossed, her eyes blazing.

Inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Foundation’s Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2004, Guy was honoured with the Americana Music Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award for Songwriting in 2005. His music has influenced numerous musicians over the years. In 2011, a double album called THIS ONE’S FOR HIM: A TRIBUTE TO GUY CLARK was released and featured Willie Nelson, Lyle Lovett, Rosanne Cash, Emmylou Harris and many more covering his songs. Last year a documentary, Without Getting Killed or Caught: The Life and Music of Guy Clark, which follows Guy’s journey as he moves from Texas to Los Angeles to Nashville to become one of the most revered songwriters in America was released.

Having other artists sing and record his songs had always been a bonus for Guy, and though he never actively chased after people to cut his creations, he was always associated with proactive publishing companies that made sure his songs got out there to producers, a&r men and the singers.

“I like mailbox money. I write the songs for me to do, and when somebody else does them, I just adore it,” Guy told me in 2007. It was around the time that once again his songs were being unexpectedly covered by mainstream country acts such as Brad Paisley, who included Out in the Parking Lot on his multi-million selling TIME WELL WASTED album or George Strait who recorded Texas Cookin’ for his IT JUST COMES NATURAL 2006 album. The song had been written some forty-odd years ago and was the title cut of Guy’s second album. He probably thought the song had run its course, but fellow Texan George thought otherwise. It was an album that sold in excess of three million copies, bringing Guy several thousand dollars in royalties.

Having said that, Guy Clark was never one of those Nashville songwriters who could roll out dozens of hits. Some of his idiosyncratic songs did receive country radio airplay, but most were jewels that can only be enjoyed when popping open a Clark CD (in his case, the plastic ‘jewel case’ is aptly named). His best-loved works are considered classics not because of the general public’s adoration or monetary windfalls, but because they contain words and melodies that captivated audiences and inspired smiling awe in other writers who continually appreciate Guy Clark’s knack of passing along wisdom and detail, not judgement.

His honest, off-the-wall, gripping musical storytelling evokes the world of the vanished small town, contemporary cowboys, blue-collar workers, rural get-togethers, drive-ins, gas stations and roadhouses. Full of tangible, real-life traits, Clark’s characters have histories and names and dilemmas and decisions. His songs enter the lives of these people and keep the listener interested in what happens to them. His vocals had an immediate, conversational quality: a great country voice seasoned with experience and marked by a depth of character that came from the soul.